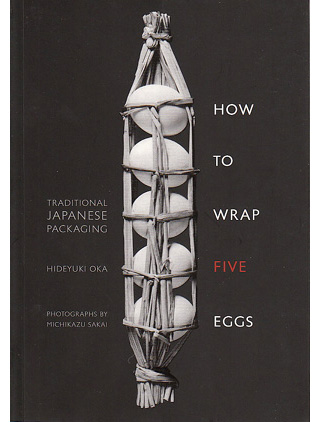

How to Wrap Five Eggs – Traditional Japanese Packaging, by Hideyuki Oka. Photographs by Michikazu Sakai.

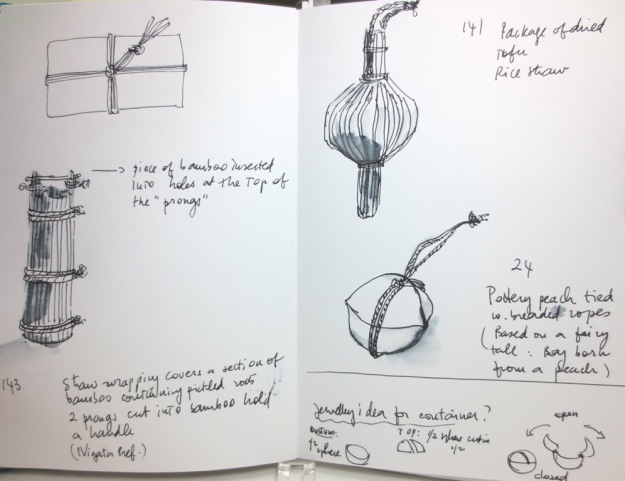

For years, I lugged around a dog-eared copy of “How to Wrap Five Eggs”, a coffee-table size book from my local library. Knowing that it was both out of print and unaffordable, I made dozens of drawings from the gorgeous black and white illustrations so that I could revisit them and mine them for ideas later (until I had received too many angry reminders from the library, and had to reluctantly return the book). I found everything I was looking for, and much more: timeless designs, both practical and beautiful.

Hideyuki Oka (1905-1995), a renowned Japanese graphic designer, collected traditional Japanese packaging and his collections were regularly exhibited around the world. A book featuring over 200 traditional objects from his collection, with illustrations by Michikazu Sakai, and commentaries by Oka, was published in 1967. A second edition came out in 1975 under the title “How to Wrap Five More Eggs”. These are pricey, oversized books, with gorgeous black and white photographs, that, as I said, are unfortunately out of print. However, in 2008, Shambhala Publications reissued the second book inexplicably under the title of the first book “How to Wrap Five Eggs”. As a paperback, it is now quite affordable, and also, thankfully, much easier to lug around!

When searching for inspiration and new ideas, I always prefer to look at other mediums. By avoiding jewellery, I am more likely to come up with less predictable, fresher ideas. Also, I find that most design solutions can be translated from one medium to another. This book is an excellent tool for the design process. It shows what makes a “good” design – a balanced relationship between beauty and function.

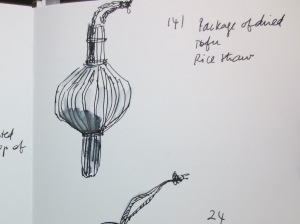

(Above) A package of dried tofu slices made of rice straw. It reminds me of the lavender potpourris my grandmother would make every year at the end of the summer. The bundle of long-stemmed flowers was tied tightly together, then bent onto itself to keep the flowers on the inside. A silk ribbon was threaded through to keep it from breaking and spilling its contents on the linens. Simple, but effective.

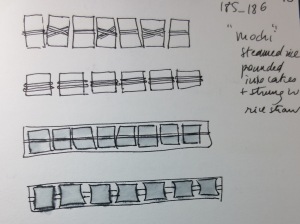

(Above) Tofu and “mochi” (steamed rice) pounded into cakes and strung with rice straw. Can be hung from the ceiling and used as needed. Ordinary, everyday products are beautifully and elegantly packaged. The strong graphic lines of the straw create a very pleasing rhythmical pattern.

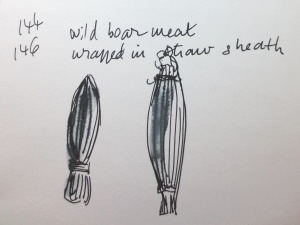

(Above) Basic packages made from natural materials and designed to carry, store and preserve various food items. Palm leaf, and a sheath of straw.

(Above) Sampling of food from a restaurant in Tokyo wrapped in an unadorned package – except for the elaborate knots of the straw rope. This was meant to be given as a gift. It is quite understated, but done with great care and consideration. According to Oka, “What is the use of a package if it shows no feeling?”

(Above) A section of bamboo covered with straw, used as a container for pickled roots of mountain burdock. Rustic looking, but its shape is perfectly suited for the long roots of burdock. The handle is a small piece of bamboo inserted into holes pierced into two prongs protruding from the bamboo tube – a simple, but elegant solution that could be easily translated into metal.

(Above) Container for candies, from Okayama Prefecture. Pottery in the shape of a peach tied with braided ropes. The design is based on the fairy tale of Momotaro, the boy born from a peach. The bottom part of the container is a half-sphere; the top is made of two domed sections. This is another design that could be adapted to metalwork, for a small locket or a larger scale vessel, with a lid articulated on hinges.

What I have presented in this post is a small sampling of what can be found in Oka’s book. In this selection, I chose to focus mostly on simple packages made with everyday natural materials, whatever was at hand, like straw, leaves and bamboo. “How to Wrap Five Eggs” offers many more examples of wrappers, boxes, baskets and various containers, some more intricate or less rustic, and using clay, paper, wood or fabric. Regardless of the choice of materials, no matter how humble they might be, the craftsmanship is always exquisite; whatever the technique (ceramics, wood carving, basketry, etc.), every piece shows a careful attention for the simplest of details, as well as ingenuity and creativity. These are valuable lessons on how to apply smart, elegant solutions to design challenges; timeless in that they can still be applied today, even with modern materials.

I will leave you with one final quote by Hideyuki Oka : “… what we have lost for sure is what this book is about: a once-common sense of fitness in the relationships between hand, material, use, and shape, and above all, a sense of delight in the look and feel of very ordinary, humble things.”

“How to Wrap Five Eggs – Traditional Japanese Packaging”

By Hideyuki Oka. Photographs by Michikazu Sakai. Weatherhill, an imprint of Shamhala Publications, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-1-59030-619-2