Lately I have felt the need to reconnect with less traditional techniques, and to be a bit more spontaneous in my approach. In my “side-gig” as an art history instructor in our Jewellery Programme, I had been looking at the work of the Abstract Expressionists, namely Jackson Pollock. The photographs and film of the painter shot by Hans Namuth in the early ‘50s show Pollock at work. In these iconic images, Pollock is seen moving about the large canvas laid on the floor, leaping and dripping or throwing paint right from the can. He appears to be totally immersed in the act of painting, an intense, gestural process; at some point, saying: “A painting has a life of its own; I let it live”. I watched this clip over and over again and knew that I wanted to work in a more instinctive manner, to respond to the metal as it moves and shifts, to be more engaged with it. I needed to put the “action” back into my work. I should also mention the paint-splattered shoes and the dangling cigarette, oooh, so cool. I wanted that too, or whatever the equivalent is for a goldsmith (minus the cigarette, of course).

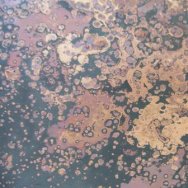

Taking Pollock and the Action Painters, and their direct and immediate approach to painting as a point of departure, I decided to tackle a series of brooches (brooches, being less constraining and offering a larger “canvas” so to speak). I would riff on a few abstract shapes and create three-dimensional forms based on them. Copper, a very ductile and malleable metal, was the perfect candidate. It also lends itself well to patinas and will take on rich colours, sometimes even quite painterly.

Using corrugation and fold-forming, techniques that are fairly quick and hands-on, I was able to shape the sheets of metal rapidly, in a gestural and energetic manner. I recommend Patricia McAleer’s book Metal Corrugation, Surface Embellishment and Element Formation for the Metalsmith, 2002, Out of the Blue Studio (ISBN: 0-9715242-0-3), a very thorough and handy manual on corrugation. Fold-forming, a technique developed by Charles Lewton-Brain (several excellent publications available, see: Brain Press Publications) is a process that is both technical and playful, where the material is folded and unfolded repeatedly to form three-dimensional structures. Both techniques only require a few tools and simple equipment. For corrugation, I used the Bonny Doon Engineering micro-fold brake #115090 (available at riogrande.com). Fold-forming does not require any special equipment other than a rolling mill. Free tutorials are available on ganoksin.com.

So, this is what I have been doing so far: These brooches are a sampling of a series of impromptu sketches or studies in metal. Rather than cleaning the metal by pickling it after annealing and soldering, I have left it in its natural state, oxidised, covered with a patina of warm, earthy colours. For me, this is a bit like Pollock’s paint-splattered shoes – evidence of the process of working the metal.

Rolling, folding, unfolding, shaping. Action!

Acknowledgements: Thank you for your research, Andrew!